Breath Soon, 2022

The critical texts presented here offer an analysis of Benoît Barbagli’s work. They highlight his close relationship with ecology and his place in the contemporary artistic landscape. Written by critics, curators and philosophers, these writings bring diverse perspectives, reflecting a variety of approaches and reflections on art, nature and the current issues of our time.

storm and momentum

2022

by Rébécca François

Curator, Musée d’art Moderne de Nice

Benoît’s experiments hybridize with stealth. They involve different mediums (painting, sculpture, photography, video, sound, publishing) in the performative field. Their multi-faceted approach is rooted in the interventionist and appropriationist approaches of the second half of the twentieth century.e century before escaping into the background, tracing an undetectable dynamic.

Declaring art as a pretext for life, “fantasizing the ultimate piece as a simple breath: a breath”, Benoît is part of a Fluxus heritage where life is no longer theatricalized. Here, the poetry of the ordinary is grafted onto a hymn to nature stripped of all bucolic vision. However, Benoît doesn’t intervene in natural environments like Land Art artists; he doesn’t modify the landscape, nor does he preserve or heal ecosystems.

Benoît’s casual attitude to art history can be unsettling. Far from being a driving force for creation, the artistic quotations that sometimes surface are apprehended in an uninhibited way, in the mode of copyleft , as a free development or diversion. A world away from the postmodern artist who multiplies references, Benoît turns his gestures into poetic images stripped of their historical anchorage; a position-reaction to a contemporary art scene in favor of the here and now. “Inconsistency is not insignificance” said Marcel Duchamp.

On the mountain range of Annapurna, on the Massif du Mercantour or on the shores of the Mediterranean, Benoît walks, bivouacs, climbs, swims, snorkels to create gestures that look like conquest but remain futile and ephemeral. He rubs shoulders with and courts nature, throwing himself into the void or the depths of the abyss to offer, for the space of an instant, a bouquet of flowers to the Earth[Les Tentatives, 2014].

The ascent, the vertigo, the lure of the void, the exhilaration of the depths give the embrace a sexual drive. Primordial energies – water, fire, air, earth – and elemental qualities – hot, cold, dry, wet – are summoned, and with them various nocturnal and diurnal landscapes – mountains and sea, cliffs and gentle lakes, the heat of the sun and the icy whiteness of snow.

The question of the nude in the landscape appears to be a necessary counter-field to the anthropocene era. No longer displaying the central, narcissistic position of the human or “I”, it calls for a horizontal, pacified relationship with the world. It’s built on a desire to act, to react, to take charge.

The erotic offerings experiment with the meshes that connect humans to nature. A plea for ecosophy, a call to feel the vital impulses unfold there. Meditation establishes itself as a form of peace[2016] . Visits _[2014] exult the pleasure of connection and interaction. Nature is no longer an idealized place of retreat, it is a privileged and intimate partner. She is where the wind blows.

Benoît promotes moments of artistic synergy through eco-solidarity actions. He initiates collective creation sessions in a joyful, festive atmosphere, where the figure of the author and authority is questioned. Together, they drop to the bottom of the water as if in a deep sleep [We tried to fall asleep underwater2018], play the trumpet on the open sea [There’s a link between music, water and life2019], run naked in the snow [Sunburn, 2019].

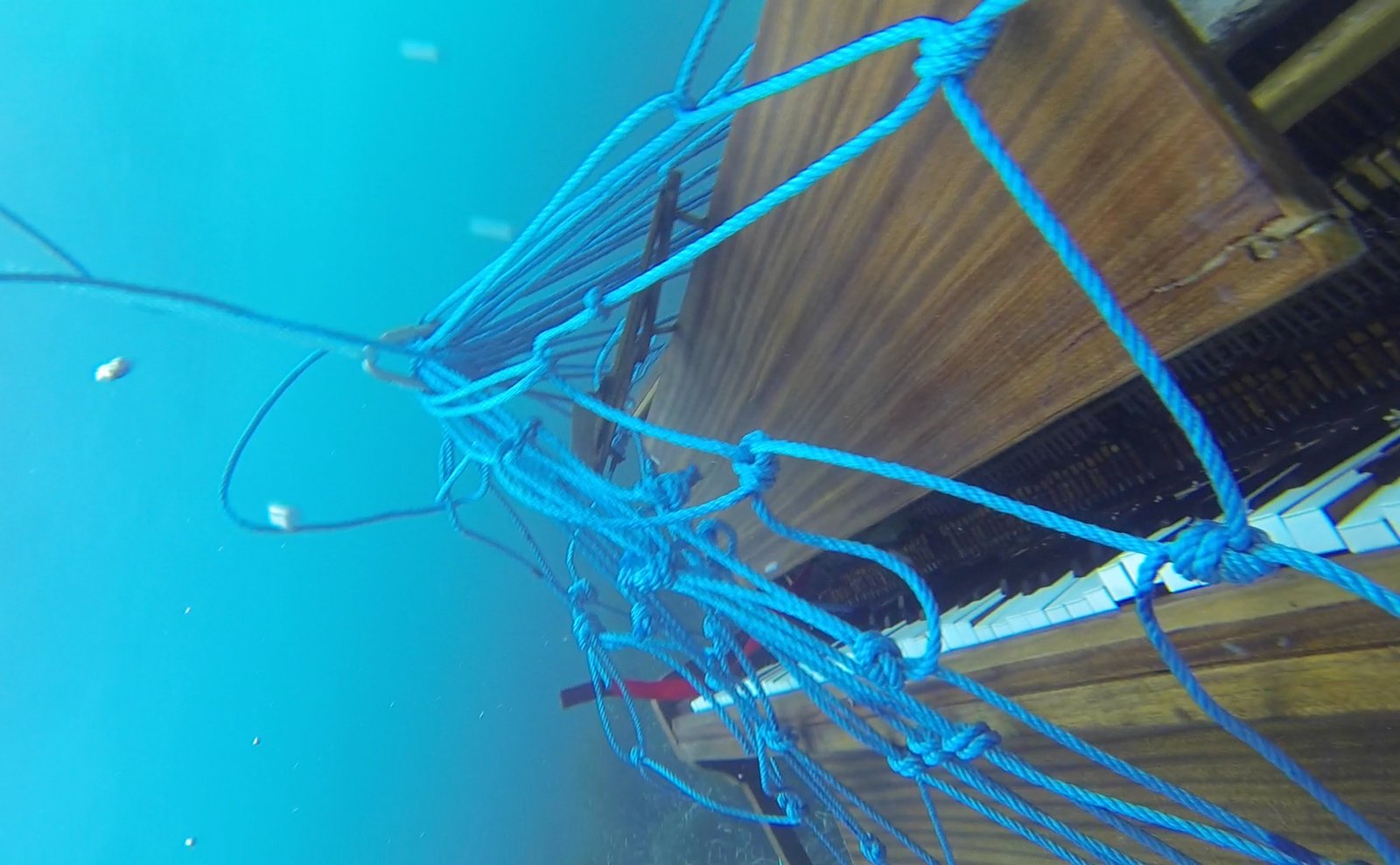

Some expeditions are permanent, ephemeral or nomadic in the landscape, calling on the help of companions with specific skills and qualities. With a naval architect[Marc Risé] , musicians and amateur freedivers, he immerses, for the time of a session, a piano “infusing a musical wave in the depths of the sea” [ La tide de la trépidation , 2015]. Accompanied by climbers [Félix Bourgeau, Audrie Galzi, Tom Barbagli], he affixed a bronze cast (weighing around 20 kg) of his arm holding a real bouquet of flowers, doomed to disappear if not replaced[Ici la terre, 2014]. With a cameraman friend, he makes a stele of burnt wood travel in the middle of nature like an open interstitial door on the other side of the mirror [ Monoxyle , 2019].

Nature is also a privileged partner. In Athens, with artist Eri Dimitriadi, he attempts to capture the shape of water on land or under the sea[Ocean mémoria, 2017- ]. Alone, he throws natural ink, made on site, into the landscape to smear a canvas placed below in a form of cosmological co-creation[Ecotopia, 2016-2020].

This propensity for collaborative work crystallized in the 2018 birth of a collective with variable geometry (Tom Barbagli, Evan Bourgeau, Camille Franch-Guerra, Omar Rodriguez Sanmartin, Anne-Laure Wuillai) and fluctuating names (Azimuth, Palam) magnetizing shared eco-solidarity desires and ideals. The collective and walking in the mountains becomes a work process, a way of inhabiting the land [ Azimuth , 2018; Beneath the Ice, Water , 2019].

Benoît is one of these nomadic spirits, trying to open up an exploratory field where energies circulate freely until the links between experience, pleasure and creation become inextricable. Witness his manifesto and epic texts, and his editions[Ici la terre, 2015]. The expeditions unashamedly take on a lyrical flight. This reminiscence of Romanticism, far from being naive, seems to evoke what this past can say in the present so that humans are no longer facing nature, but with it.

In this sensual activism, the enjoyment of freedom continues to exult again and again until it creates a momentum of political and societal life. Collective commitment – and not community – becomes procession.

Thus, they raise the point armed with a bouquet[Révolution naturelle, 2019-2020], love each other at night in the streets of the Exarchia district -a place of self-management and citizen initiative in Athens[ACAB, 2017]. With artist Aimée Fleury, they fuel and cultivate the fire of freedom […The liberation, 2020] in a kind of processual, shamanic ritual reminiscent of his plastic research into telepathy, synesthesia and trance [Body2013] or his LSD compositions [Water deployment, 2011].

These works, moments of life engaged in a better tomorrow, do not always participate in an eco-responsible reflection that would be more in tune with practice. But their nature lies elsewhere, immaterial and elusive. They crystallize in the emotion they generate, in the call to freedom, the storm and the momentum they instill.

Natural revolution, 2019-2020

Body and water

2022

par Elodie Antoine

Art critic

“Proust (…) clearly set himself the task of inexorably blurring, through extreme subtlety, the relationship between writer and character: by making the narrator not the one who has seen, nor even the one who writes, but the one who is going to write (the young man in the novel – but, by the way, how old is he and who is he? – wants to write, but he can’t, and the novel ends when writing finally becomes possible), Proust gave modern writing its epic: in a radical reversal, instead of putting his life into his novel, as is often said, he turned his very life into a work of which his own book was like the model.”

Roland Barthes,

The death of the author,

1967

From

Land,

water, the body and

art

A series of photographs Leaps of love and Expressing an emotion of love (2014) à There’s a link between water, music and life (2018) and Natural revolution (2020) through to paints Ecotopia’s inkjets (2020), Benoit Barbagli’s work embraces land, sea and sky through the prism of the body.

His photographs feature nude bodies, faces adorned with flowers, and arms reaching for the sky. His body lets the elements do their work – their work and/or his work. This was the birth of painting, not unrelated to his elder brother, Yves Klein, but a contrario of the latter, without any demiurgic will. And if the subjects of his photographs are “guided” and/or accompanied in their actions, they do not replace the artist’s brushes in a modernist logic of pictorial renewal. They are bodies – neither objects of the conductor’s desire, nor pictorial tools, nor models – free bodies to whom the artist offers collective experiences in the middle of nature – in the middle of the forest and the waters. The shots are pretexts for a collective experience in places mostly unknown to these bodies. It’s more a question of discovering a place and an environment, a quest for the potential of natural spaces.

Through shared experiences, bodies gradually find their natural place amid the elements: sea, lake, mountain, forest. The titles of the photographs (

Underwater mythology

,

Underwater ritual

,

At 90° above the fire

) bear witness to this close relationship with the elements.

The author also observes an adelphity of bodies, which he readily associates with the emergence of the sacred. It’s as if these acculturated bodies have found, by dint of frequenting and practicing the natural environment, a pre-cultural state that leads them to become one with nature, to curl up in it.

This quest is not unrelated to that pursued at the dawn of the seventies by artists who decided to make nature their studio: walking, running, tracing, marking, finding, gleaning, collecting, laying, moving.

Benoît Barbagli’s performances revive this special relationship with nature. That of those who, through their walks, wanderings and drifts, have sought to experience a relationship with the world outside the modern, arch-modern world. A world, in the eyes of some of them, dehumanized, a world without horizons. The English countryside, the Nevada desert and the hinterland of Nice appeared to them as a horizon, a possibility, a territory to explore far from the omnipresence of city noise and culture.

Benoit Barbagli proposes to his fellow travelers not a solitary experience, but a collective one – a federative experience to create a common, social body. A social body far removed from the conventions and rituals of contemporary consumerism.

From the death of culture to the death of the author

Back in the workshop, what happens to this social body? What is its status, its place in the author’s work?

Who is the young man in the pictures? Is he the subject? Is he the author? Is he the instigator? Who’s the eye behind the camera?

Is the alleged author the subject? What do these photographs tell us? Her author, her story, her body, her youth?

Where’s the author?

Who are the characters? Where do these submerged bodies come from?

Benoit Barbagli inexorably blurs the lines. Just as Roland Barthes looked at Marcel Proust’s work, Benoît Barbagli sometimes appears in his recent photographs, and although he remains the author of them, he willingly takes a back seat, not behind the camera.1but rather behind a collective body – the collective body that gives meaning to its photographs – a utopian body?

And what if this return to nature, this social body, this union with the natural world, however transitory and fleeting, were, in his eyes, the image of a possible relationship with the world to come?

The “world after” we’ve heard so much about. A radiant future where ecology becomes one of the presidential candidates’ hobbyhorses, where air travel is limited to a certain mileage in order to preserve our skies, and our earth too.

This sweet dream of conscious citizens – aware of the world they live in, not just their own, but that of others – beyond the Atlantic, the Amazon, the Dead Sea and the Adriatic, the Carpathians, the Gobi and Negev deserts.

Forms of freedom: nesting, leaping, emancipation

The nest, the cocoon

From the Bay of Villefranche to Lac de Saint Cassien and Cap Ferra, bodies seem to curl up and move in the newfound freedom of amniotic fluid.

Limbs together, apart, symmetrical, asymmetrical, submerged bodies standing out from the green water, alluvial deposits forming more or less regular circles. The bodies themselves draw a circle in the water, a circle that echoes that of the watermelons in

Dead sea

(2008) by Sigalit Landau.

The circle – this uninterrupted, closed-circuit line – is reminiscent of the nest in which birds are born. Nest, cocoon, circle naturally take on protective connotations. Sometimes they evoke a desire to be at one with nature, like Nils Udo’s nests:

Le Nid,

1978 ;

Au jardin du paradis,

1979 ;

Habitat

, 2000 ;

Nid d’eau

2001; and Andy Goldsworthy:

Turn Hole

, 1986.

Whether on earth (Noël Dolla : Neutral comment no. 2, 1969; Spatial restructuring n°3, 1970 ; Spatial restructuring n°5, 1980 ; Spatial restructuring n°122020); Robert Smithson: Spiral Getty, 1970 ; Spiral Hill, 1971 ; Amarillo Ramp, 1973 ; Sod Maze1974; Hervert Bayer: Mill Creek Canyon Earthwork1979-82; James Turrell : Roden crater (looking northeast)1977-present; Richard Long : Stone circle, 1976)

in the water (Christo and Jeanne-Claude,

Surrounded islands

1980-83) or in the air (Dennis Oppenheim :

Wirlpool, Eye of the Storm

1973), the circular form is at the heart of the artists’ work in nature. The circle is reminiscent of ancient constructions, notably Stonehenge (a megalithic monument erected between 2600 and 1000 BC in Great Britain).

Could this crown, this circle, also be the image and/or form of withdrawal? The one experienced by a large part of the world’s population between December 2019 and June 2020.

The jump

Another form of freedom is jumping. Think of parachute jumping or bungee jumping. While the weight of a body in a vacuum may frighten some people, for others it’s a guarantee of freedom, much like that experienced in water, from amniotic fluid to seawater.

From the leap into the void (Yves Klein and Benoît Barbagli) to the one observed Barbagli’s recent images in the shallow waters of Lac de Saint Cassien. of Lac de Saint Cassien, the bodies embody a freedom regained, won.

These bodies seem to crystallize a new-found freedom. Immersed in water, they no longer suffer the pangs of gravity, allowing them to move freely. And yet, these bodies are stopped in their tracks by a still image. Barbagli shows this

hic

et

nunc

of freedom – that furtive, transitory, fleeting moment, to use Charles Baudelaire’s term for the painters of modern life. In this way, the photographer attempts to give this moment an eternal dimension.

By immersing his images (

Double immersion

2022) in salt baths (boron salt), he not only re-enacts the immersion of the bodies, but also endows them with a concrete surface, a crystallized salt crust. The photographic moment appears like a revelator, while the time spent in the studio (immersing the photographic prints in salt), on the contrary, is more on the side of disappearance.

These images crystallize something – appearance, disappearance, momentum.

Emancipation

In 2007, the Invisible Committee – a collective of anonymous authors – published

The Coming Insurrection

(Edition La fabrique), a political, economic and social analysis of France at the time, followed by an application manual for mobilization, organization and revolt:

Not to wait any longer is, in one way or another, to enter into the logic of insurrection.

2

.

At the end of 2008, the intellectual and philosopher Julien Coupat was accused of sabotaging catenary wires on train lines, and of being the alleged author of the aforementioned book. In early December, Coupat was indicted along with nine of his friends, and jailed in March. Artistic, militant and literary circles mobilized. In the space of a few weeks, the accused of the Republic became a hero in the eyes of a youth with no illusions about the political class of the day.

In 2009, another collective, Tiqqun, published

Contributions à la guerre en cours

a collection of three texts previously published in October 2001 in the magazine

Tiqqun 2

. The authors call for a rally. They declare in the very first lines of the book:

- The elementary human unit is not the body-individual, but the life-form.

- Life-form is not beyond bare life, but rather its intimate polarization.

- Every body is affected by its life-form as by a clinamen, a penchant, an attraction, a taste. What a body leans towards also leans towards itself. Again, this applies to every situation. All inclinations are reciprocal

3

.

–

In this introduction to the text “La guerre-civile, les formes- de-vie”, the authors situate

the body

at the heart of human concerns, particularly in its drive towards revolution.

This praise of the body not as tool or object, but as “form-of-life”, is not unrelated to Benoit Barbagli’s artistic project. The performer’s body is not an extension and/or image of the artist’s body. He is a

medium

that becomes incarnate, anchored in life.

In 2009, a group of intellectuals, including Jacques Rancière, Slavoj Zizek, Kristine Ross and Alain Badiou, published

Démocratie dans quel état ?

(La fabrique). Inspired by the investigations carried out by the Surrealists in the 1920s, the authors attempted to question and take a fresh look at the concept of democracy.

The social body staged by Benoît Barbagli in his latest creations extends, in its own way, the philosophers’ questioning, perhaps suggesting that the issue is still open today. Works that, like the

Gestes d’amour

of

Coup de soleil

and

La libération

advocate a form of emancipation, a celebration of giving and freedom – an ode to life.

1 He is not the eye behind the camera, as the photographs are taken by drone in

geostationary position.

2 In invisible committee,

The coming insurrection

La fabrique, Paris, 2008, p. 83.

3 In Tiqqun,

Contributions to the ongoing war

La fabrique, Paris, 2009, p.15

It’s like a link between water, music and life ,

2018

Underwater Ritual, 2021

90° above fire, 2020

Origin of Joy, 2021

Coup de soleil, 2019

Diving into the heights

2017

by Michel Remy

University of Nice

Benoît Barbagli, or diving in the heights.

It is between the middle and the end of the 18th century that has been confirmed the philosophical and moral doubt as to the power of man over nature, which classicism proclaimed loud and clear. At that time, nature gradually imposed itself against the alleged domination that man thought he was exercising over it. Birth of the English garden, fascination with ruins, discovery gothic entrails of this same nature, apotheosis of the romanticism of Bernardin de Saint Pierre, Byron, Lamartine, Hölderlin, Shelley, Hugo and so on…

With them, a sensibility takes shape in search of itself, a “thought prey to the excess that engenders it” “under the rubble of our abolished certainties” according to the beautiful phrases of Annie Le Brun. The mountains, like the underground passages of castles, then become the places where the soul of the world, the spirit which wells up both from the geological strata and from the vertiginous reliefs, where this soul and this spirit amazes us and invites us to dialogue with them with regard to infinity. The famous experience of William Wordsworth as a child, seized with terror in the shadow of the rocks on which the night was settling, Shelley in terrified admiration in front of Mont Blanc, Lamartine and its lake, Musset and the howls of wolves, all signed this endless dialogue…

Without in the least indulging in ridiculously disproportionate comparisons, we believe that Benoît Barbagli is one of those who, heirs to this “diving into the heights” – if I may this oxymoron – succeed in suspending rational thought, to “stripping off these bonds of mortality” and to transcending oneself, but remaining solidly here. Benoît Barbagli’s work is a performative work, that is to say a staging of both himself and sea and mountain landscapes. We are tempted to see, albeit hastily, an affiliation with the Land Art of the seventies, but we must quickly say that it is a Land Art which would go beyond too dry an objectivity and which would be inseparable from a deep spirituality, without this term having anything religious about it. It is also not without importance that he decided, in order to facilitate this escape from self, to seek this soul of the world in India and in Nepal, cradles of a religiosity without religion, where spirituality is the banal daily life of men, where one can only be seized with vertigo – and isn’t vertigo the forgetting, dreaded or hoped for, of gravity? ? Exoticism is elsewhere. It is to come out of oneself.

The confrontation with space, through its lyricism and its exaltation of the deep self, expresses in Barbagli the need to find the measure of man outside of all visual and moral conditioning. As if, by plunging into a mountain precipice, we discovered what is at the bottom: our body undressed in its civilized tinsel. This is where the nudity of certain bodies takes on meaning from Barbagli. Doesn’t nudity represent separation, abandonment of the world of false appearances, a kind of self-reappropriation, in order to reach the shores of a truth that has eluded us and enter into an intimate relationship with the otherness? This relationship then leads to an interpenetration of man and the cosmos, of the self and the big other, in which the two terms of the relationship find themselves in the same state of original purity – an attempt by the self to meet the Other at the same level and to abolish what risks differentiating them. Let’s look at some photos: whether the body adopts the fetal or curled up position, whether it plunges into the ocean of time in an offering of itself, in an ithyphallic self-forgetfulness or whether it defies gravity and “enters into lightness” ( as they say to enter into religion!) by keeping their city costumes on the prow of a rock, the spectator finds himself precipitated into another dimension of vision, a wild vision.

Paradoxically, what secretes this savagery of vision is the staging, the pose, the perfectly thought-out composition which ensures that the bodies are in no way irruptive or disruptive but are on the verge of melting… This is where photography comes from to the rescue of a work that should disappear, because this work, wild, can only be ephemeral… This is where the concern for poetic composition changes the nature of photography which, instead of being comfortably and banally documentary , reveals an immense imaginative potential. Breton said that “the eye exists in the wild state”. But that eye who is well that of Magritte, of Miro, of Masson or of Ernst when they are painting and blending into “the hidden territories of the unconscious”, is not that eye also what becomes of the viewer’s eye the very moment it discovers what they have painted? Isn’t the “savagery” of this vision communicated from one to the other? The same joins the other, the physical the metaphysical, the ephemeral the eternal, we are in full immanence…

Here the earth…yes, but also, here the spirit. – and the imagination!

There are places where the spirit blows, and Benoît Barbagli shows them to us…

The visit, 2014

Beneath the chaos, life

2021

by Pulchérie Gadmer

Art critic

Benoît Barbagli’s studio is vast. Ocean, river and mountain are his performative spaces. Art arises there, a vital emergence within the collective. His plural and multi-medium proposals hatch in itinerant gestures. Art moves in nature.

In his peripatetic devices, the path makes sense, the nudity is candid, and the work manifests itself in upsurges. The configurations are multiple, the rituals varied and, often, the expedition that leads to the artistic experience is done with visual artists. His camera is described as “flying”. It passes from hand to hand and the signature is frequently shared or collective.

Benoît Barbagli explores borders. He draws from the substrate of creation in search of its germinations from shared nourishment. The Mountain creates as much as the sea, as the artist friend, by his presence, by his movement, by the principle of life, essentially random, which moves him. Art captures moments of the Living which always manifests itself where we least expect it, in unheard-of sequences that we sometimes struggle to capture in their deployments. With humor, lightness, strength and delicacy, Barbagli invites us to capture the moments and encourages us to consider them in their ephemeral beauty. An ode to Vitality.

The four elements are recurring. They animate and structure the artist’s series in Heraclitean bursts. Fire, water, air, earth. Benoît Barbagli’s universe is poetic, polysemous, modest, funny. He likes to “divert references from culture to return them to nature.” What makes a work? The project ? Its manifestations? He orchestrates meetings, a community is created around the project and the creative space then becomes a joyful pretext for life.

To pay homage to the living, to restore its place to it, the artist fades away, he stages, stages and yet fades with great elegance, the ego dissolves in the interconnected, I is another. Benoît Barbagli is reverse romanticism. His return to nature takes place in a peaceful setting where egotism is annihilated, where praise is stripped of pomp, where art emerges in its simplest expression.

In the Mediterranean Sea in winter, a hand holds out a bouquet in the icy water, the fertile sea is also deadly lately. Eros and Thanatos come together, amorous ardor and mortuary homage are two sides of the same mirror. In an attempt at love by torchlight, a naked body throws itself off a cliff, tomb of the diver or inextinguishable passion? The moment is in suspense, an unresolved space subject to the projections of the viewer. Grace, fall and rebound – or not, are part of the whole thing. Bodies carry a stone under the troubled surface of a lake, the emergence of a new Atlantis or the Sisyphean perspective of an inevitable landslide after yet another attempt? The artist and his acolytes bring their stone to the visual edifice.

Benoît Barbagli is the sherpa of the mountain, he transports his paintings there so that the latter can create. He removes the museumification of the woman’s body by returning it to the earth. He picks up the spark igniting the beam. He walks on the Anthropocene by questioning the stars, born of chaos.

Born from earth, 2014

Supra conceptual

by Camille Frasca,

Curator at the Musée Picasso

Benoît Barbagli is what one might call a supra-conceptual artist. Born in 1988 in Nice, he took classes at the Villa Arson from 2010, where he learned each year to question himself. He is advised to always look for a beyond, to push further, to constantly question. This turn of mind then fuels his artistic research. It multiplies and diversifies practices, creating bridges. Works by gestures,

teeming with ideas, boiling.

The text is the binder to understand the works. And allows him to satisfy his insatiable desire to always go further. Because Benoît likes to find things that are infinite, unfinished, “without edges” as he says. […] We’d like to classify him as part of a post-Land art movement, because what often comes up is the escape from the gallery, to run around in the public space. But that would imprison it in a field of references which it does not necessarily claim. Benoît constructs his own story: the other crucial aspect in his work is the narration. Language is for him an almost plastic material, each project containing a narrative germ that is formed and becomes more complex as ideas are born, live and die in Benoît’s head.

Edgeless, 2020

Playing the piano at the bottom of the sea

by Thomas Golsen,

Professor of Art History at the University of Lille

L’imersion, 2014

The poetic engineer, 2015

by Benjamin Laugier

Curator at the New National Museum of Monaco

Tied with a strong relationship to nature and science, his performances can thus be orchestrated by complex devices or require only the simplest device.

His Visites can sometimes recall Philippe Ramette’s postures when he himself invokes Caspar David Friedrich’s Le Voyageurc ontemplant une mer de nuages.

For Tide of Trepidation, he harnesses a piano to a pyramid-shaped raft. Connected to a winch, the piano is immersed to be played in apnea. This tribute to the Swedish pianist Esbjorn Svensson, victim of a diving accident, draws on Barbagli’s many sources of inspiration. Music therefore plays a central role even when it is not being played. The background of certain actions, it is often induced like a tune that one hums after a fortuitous synaptic connection.

Here, clay is a simple, romantic gesture that actually requires a certain dexterity. Clinging to the side of the cliff, a bronze arm holds a bouquet of flowers. Vertigo of the love of emptiness.

In contrast, Tentacle 115.5° is a latex prosthetic tentacle with 128 magnets arranged in the suction cups according to the Fibonacci sequence, i.e. 2 exponent 7. A new climbing project, this one hypothetically involves climbing Bernar Venet’s sculpture 115.5°, installed in the Albert Ier garden in Nice.

L’incarnation – ici la terre project, 2014